CENTURIES ARE REQUIRED TO CHANGE MENTALITIES, CENTURIES. YOU DON’T GET A CHANGE OF MENTALITY BY INTRODUCING A FEW FADS.

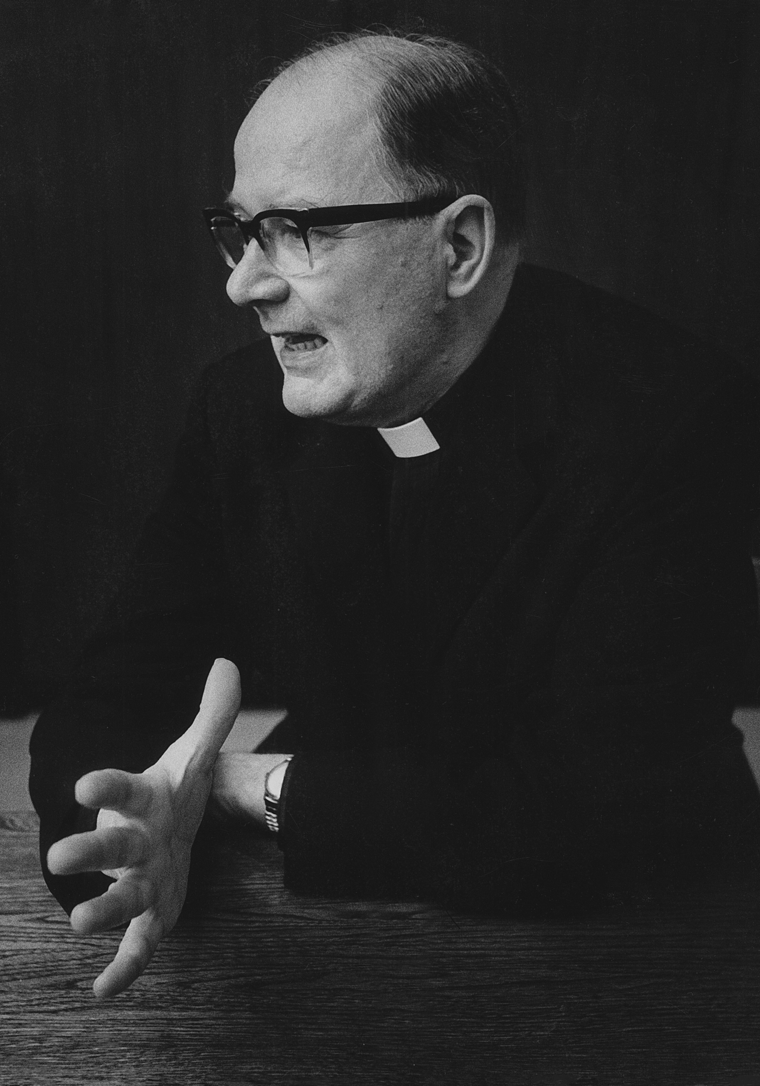

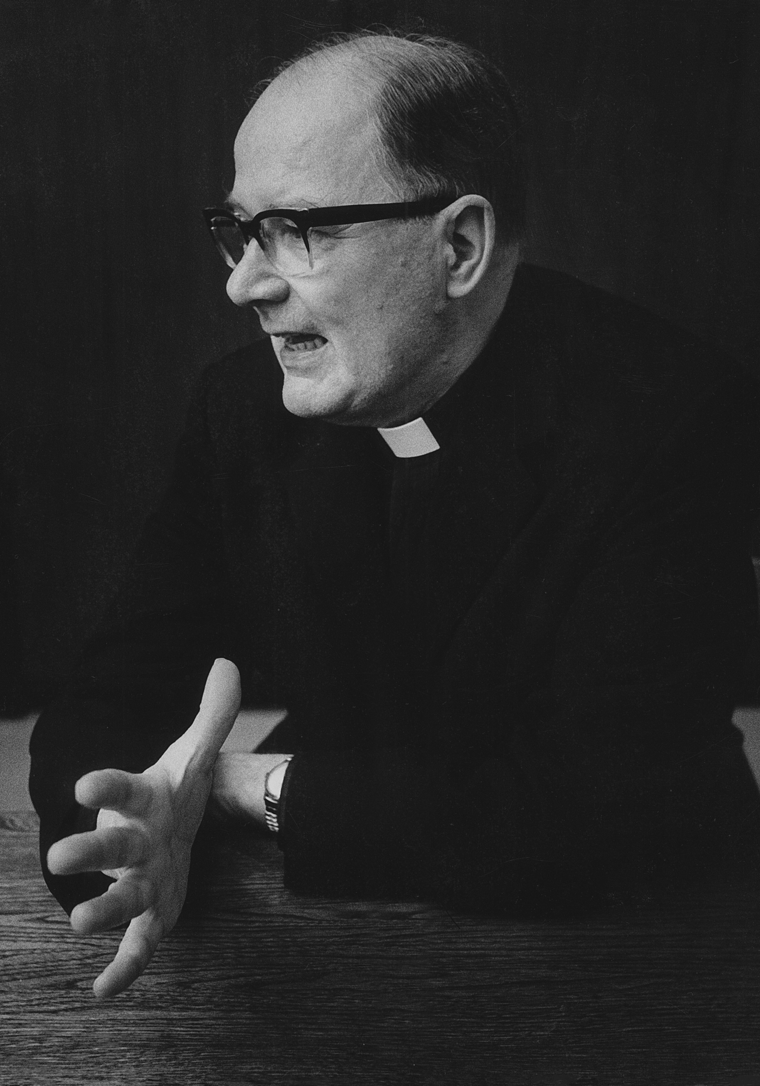

-Bernard Lonergan

About Bernard Lonergan

Bernard Joseph Francis Lonergan, SJ (17 December 1904 – 26 November 1984) was a Canadian Jesuit priest best known for his original contributions to philosophy and theological method. His intellectual program embraced philosophy, theology, macroeconomics, and the problems of method in the human sciences and historical scholarship.

As a young man, Lonergan was struck by the conquests of Marxism, which impressed on him that ideas have consequences. Marxism’s conspicuous failures, and the disaster of the Great Depression, reinforced the importance of getting the ideas right. Sent to London to study philosophy, he also took degrees in mathematics and classics. Nights he poured himself into economic analysis, convinced that a sound understanding of the economy would be the indispensable handmaid of Catholic social teaching and the chief means of helping the poor ‘in a notable way.’ Later he was sent to Rome for a doctorate in theology. Watching Europe hurtle towards the conflagration of World War II, Lonergan knew that only a theological analysis could take full account of the effects of both sin and grace in history. He set himself to work out the principles of progress, decline, and redemption.

CENTURIES ARE REQUIRED TO CHANGE MENTALITIES, CENTURIES. YOU DON’T GET A CHANGE OF MENTALITY BY INTRODUCING A FEW FADS.

-Bernard Lonergan

Lonergan’s motto was vetera novis augere et perficere: to enlarge and complete the old with the new. He felt that deep knowledge of the old, of the best traditions of Catholic thought, was increasingly hard to come by. He spent eleven years ‘reaching up to the mind of Aquinas.’ The literary fruits of this apprenticeship include two major studies of Aquinas: Grace and Freedom and Verbum: Word and Idea in Aquinas. But Lonergan often remarked that Thomas Aquinas was more widely praised than imitated. Lonergan admired Aquinas for bringing Christian thought to terms with the best philosophical and scientific achievements of his day. He recognized that, to do for our day what Aquinas had done for his, the highest achievements of the Catholic intellectual tradition must be brought into conversation with modern science, historical investigation, and philosophy—for the wellbeing both of the Church and of the world. To many, it seems that science has once and for all displaced Christianity as the only serious basis for order in the soul and society. Religion is regularly confined to the realm of private feeling. Lonergan saw there was needed a new articulation of Christian faith that could restore the Church’s capacity for intellectual and cultural leadership.

AFTER SPENDING YEARS REACHING UP TO THE MIND OF AQUINAS, I CAME TO A TWOFOLD CONCLUSION. ON THE ONE HAND, THAT REACHING HAD CHANGED ME PROFOUNDLY. ON THE OTHER HAND, THAT CHANGE WAS THE ESSENTIAL BENEFIT. FOR NOT ONLY DID IT MAKE ME CAPABLE OF GRASPING WHAT THE VETERA REALLY WERE, BUT ALSO IT OPENED UP CHALLENGING NEW VISTAS ON WHAT THE NOVA COULD BE.

-Bernard Lonergan

To fulfill this program of recovery, renewal, and development, Lonergan devoted himself to a wide-ranging study of the workings of the human mind in mathematics, natural science, common sense, philosophy, and theology. The chief literary fruit of his investigation was Insight: A Study of Human Understanding (1957), which he designed as a kind of guided introduction to the workings of one’s own mind and, ultimately, to the Maker after whose image that mind is made. In Insight, Lonergan’s fundamental question was, What is it to know? He addressed some of the most pressing questions in society and the university: Can math and science, history and literature, philosophy and theology, everyday life, love, and religious commitment be fitted together into a coherent whole? The cornerstone of Lonergan’s project is ‘self-appropriation,’ that is, the personal discovery and personal embrace of one’s own boundless wonder, thirst for intelligent answers, demand for sufficient evidence, sense of moral obligation, and openness to love.

MORE THAN ANY OTHER AUTHOR, LONERGAN MAKES SELF-DISCOVERY THE CENTRAL ACTIVITY OF PHILOSOPHY AND THEOLOGY.

-Kenneth Melchin

By self-appropriation, one finds in one’s own intelligence, reasonableness, and responsibility the foundation of every kind of inquiry and the basic pattern of operations undergirding methodical investigation in every field. In the sequel, Method in Theology (1972), Lonergan explores how reason, guided by the light of faith, can proceed in relation to the gift of God’s love, the mysteries of revelation, and the complexities of our historical existence. Lonergan recognized that the challenges of the modern world call for a transdisciplinary and collaborative response. In Method in Theology he proposed a new framework for that response.

Lonergan was a professor of theology in Rome, Toronto, Montreal, and Boston. He authored major treatises on the Trinity, Christology, and redemption, as well as numerous explorations of theological method. These writings are now being presented to a contemporary readership through our Collected Works project. His courses and theological writings were also his laboratory for thinking through the challenges to theology presented by modern science and history. He was committed to the patient and thorough development of understanding that undergirds progress.

HIS CHIEF CONTRIBUTION WAS THE CREATION OF AN INSTRUMENT OF MIND AND HEART FOR OTHERS TO USE, WHOSE WORTH WILL BE DISCOVERED NOT ONLY IN STUDY BUT ALSO IN IMPLEMENTATION.

-Frederick Crowe

Today, researchers and practitioners around the world draw upon Fr Lonergan’sachievements for their own work in service to charity, truth, and justice. Beyond the rigour of essential academic research, Lonergan’s thought has inspired programs of economic co-operation, social reconciliation, cultural renewal, personal integration, religious transformation, and university and secondary education. In quiet service to them all stands the Lonergan Research Institute with its mission to preserve, promote, develop, and implement Fr Lonergan’s legacy. It is the repository of Fr Lonergan’s archives, a hub for the production of his Collected Works, and aims to be a centre of scholarly and scientific collaboration at the University of Toronto, one of the leading research universities in the world.

Life

Bernard Joseph Francis Lonergan was born on December 17, 1904 in Buckingham, Quebec, Canada. After four years at Loyola College (Montreal), he entered the Upper Canada (English) province of the Society of Jesus in 1922, and made his profession of vows on the Feast of St Ignatius of Loyola, July 31, 1924. After two further years of formation and education, he was assigned to study scholastic philosophy at Heythrop College, London in 1926. Lonergan respected the competence and honesty of his professors at Heythrop, but was deeply dissatisfied with their philosophy, which was shaped by the thought of Francisco Suarez. While at Heythrop, Lonergan also took external degrees in mathematics and classics at the University of London. In 1930 he returned to Montreal, where he taught for three years—languages, calculus, analytic geometry, mechanics—at Loyola College. Throughout this period he was intensely concerned with economics and the philosophy of history, explorations to which he devoted himself assiduously in his spare time.

THE BASIC STEP IN AIDING THE POOR IN A NOTABLE MANNER IS A MATTER OF SPENDING ONE’S NIGHTS AND DAYS IN A DEEP AND PROLONGED STUDY OF ECONOMIC ANALYSIS.

-Bernard Lonergan

In 1933, Lonergan was sent for theological studies at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. He was ordained to the Catholic priesthood in 1936. After a year of Jesuit formation (“tertianship”) in Amiens, France, Lonergan returned to the Gregorian University in 1937 for doctoral studies in theology. On the eve of World War II, he was spirited out of Italy just two days before the scheduled defense of his doctoral dissertation. He began teaching theology at College de l’Immaculee Conception, the Jesuit theology faculty in Montreal, in 1940 as well as the Thomas More Institute, in 1945-46. In the event, he would not formally defend his dissertation and receive his doctorate until a special board of examiners from the Immaculee Conception was convened in Montreal on December 23, 1946. During these years in Montreal, Lonergan’s apprenticeship to Thomas Aquinas matured. He rewrote his doctoral dissertation on operative grace for publication as series of articles in Theological Studies, then a new journal established by the Jesuits of the United States. (The series would later be published in book form as Grace and Freedom.) He composed a new study of Thomas’s account of intelligence, ’The Concept of Verbum in the Writings of St Thomas,’ also first published as a series of articles in Theological Studies and subsequently collected into a book, Verbum: Word and Idea in Aquinas.

Lonergan taught theology at Regis College from 1947 to 1953, and at the Gregorian University from 1953 to 1964. It was during his first period at Regis College that Lonergan wrote his best known work, Insight: A Study of Human Understanding. He also wrote several minor treatises on grace and providence. At the Gregorian, Lonergan taught Trinity and Christology in alternate years, and produced (in Latin) substantial textbooks on these topics. He also gave graduate seminars on theological method. In 1964, he made another hasty return to North America, this time to be treated for lung cancer. He was appointed again to Regis College from 1965 to 1975, with a reduced teaching load to allow time for writing. At Regis, he wrote Method in Theology, the long-awaited sequel to Insight.

Lonergan was subsequently Stillman Professor of Divinity at Harvard University in 1971-72, and Distinguished Visiting Professor at Boston College from 1975 until 1983. Although frequently called upon to lecture on topics related to Method in Theology and other theological questions, in these twilight years Lonergan returned to the economic analysis that had preoccupied him in his youth. He died at the Jesuit infirmary in Pickering, Ontario, on 26 November 1984.

Influences

When Lonergan listed his intellectual debts, he usually named Augustine, John Henry Newman, Christopher Dawson, and John Alexander Stewart as important early influences. His formation as a Jesuit was classical, with a heavy dose of languages (Greek, Latin, French) and mathematics, subjects he continued to pursue when he took an external degree at the University of London. The Jesuit philosophical education was based on scholastic manuals, ”German in origin and Suarezian in conviction” (Second Collection, 263), but Lonergan had little use for them. He found Newman far more helpful; he read the Grammar of Assent many times and learned, from Newman, to face problems squarely without doubting his faith. Lonergan would later claim that Newman’s ‘illative sense’ of the convergence of evidence became, for him, the act of reflective understanding that grounds reasonable judgment.

During his regency teaching at Loyola College (1930-33), developed a keen interest in Plato’s early dialogues and the early philosophical dialogues of Augustine. In later life he often referred to Augustine’s concern for veritas, truth, and his struggle to articulate a certain priority of love in human living. J.A. Stewart’s Plato’s Doctrine of Ideas helped Lonergan recognize the importance of insight for Plato’s thought and, he explained, also cured him of any temptation to ‘nominalism’. Christopher Dawson’s The Age of the Gods effected a sea-change in his thinking about culture. He had been brought up on what he called a ‘classicist’ notion of culture—that is, culture as a permanent and normative achievement passed on by education and opposed to ‘barbarism’. But Dawson gave him an ‘empirical’ notion of culture as any set of meanings and values informing a way of life. This did not involve him in relativism, but it did mean that the radical norms for human living could not be identified with the cultural attainments of any historical group.

IT IS ONLY BY PERSONAL APPROPRIATION OF ONE’S OWN RATIONAL SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS THAT ONE CAN HOPE TO REACH THE MIND OF AQUINAS AND, ONCE THAT MIND IS REACHED, THEN IT IS DIFFICULT NOT TO IMPORT HIS COMPELLING GENIUS TO THE PROBLEMS OF THIS LATER DAY.

-Bernard Lonergan

Lonergan found his encounter with Thomas Aquinas exhilarating. He had not been impressed with Aquinas as presented in the standard manuals, but was delighted to discover that the real thing was much better than he was commonly made out to be. In Aquinas, Lonergan found the most important mentor of his intellectual career. Although many of Lonergan’s preoccupations had already emerged—an interest in the theory of knowledge, culture, the philosophy of history, and the human sciences—Aquinas imparted a decisive stamp almost everywhere discernible in Lonergan’s subsequent thought.

Upon his return to Rome as professor of theology in 1953, Lonergan began a serious effort to get to grips with the hermeneutical turn in European philosophy. In Method in Theology and its precursors—the supplements Lonergan prepared for his doctoral seminars on this topic at the Gregorian University—there is a clear preoccupation with ‘getting history into Catholic theology.’ He kept up a voracious reading program, he assimilated ideas from many quarters, but few figures emerge as decisive influences on his thought. His course was his own.

When, at the twilight of his career, Lonergan returned to the economic questions that had so exercised him as a young man, he returned too to an old friend, Joseph Schumpeter, whose History of Economic Analysis became his constant companion.

IT IS ONLY BY PERSONAL APPROPRIATION OF ONE’S OWN RATIONAL SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS THAT ONE CAN HOPE TO REACH THE MIND OF AQUINAS AND, ONCE THAT MIND IS REACHED, THEN IT IS DIFFICULT NOT TO IMPORT HIS COMPELLING GENIUS TO THE PROBLEMS OF THIS LATER DAY.

-Bernard Lonergan

For Further Reading

If you are discovering Lonergan for the first time, you might enjoy Tony Patterson’s delightful telling of Lonergan’s story (linked with permission). There is a brief but high quality entry on Lonergan in the Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Western Theology.

Compass Journal (now defunct) devoted its March 1985 issue to Bernard Lonergan. It is posted here with permission.

Frederick E. Crowe, Lonergan, and Philip McShane and Pierrot Lambert, Bernard Lonergan: His Life and Leading Ideas, are both outstanding introductions.

William A. Mathews, Lonergan’s Quest: A Study of Desire in the Authoring of Insight, is probably the most complete biography of Lonergan for the periods it covers.